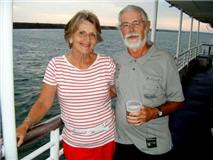

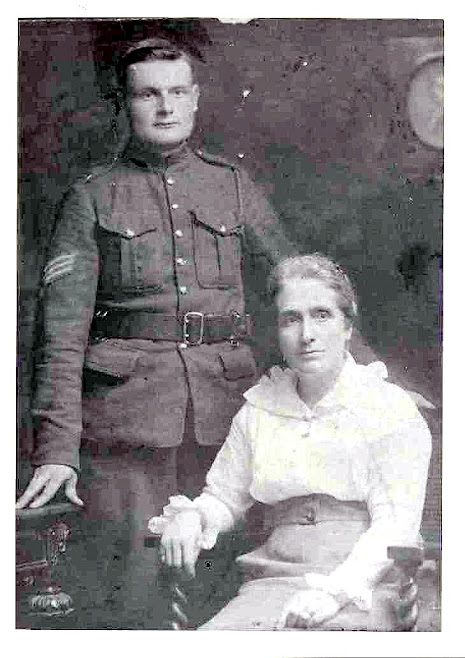

Sarah Ann Green Collins

with her son Henry Hone circa 1916

SARAH ANN GREEN COLLINS...Evans...Hone...Barnes...Breen b.1862 d.1935

A thrice married Englishwoman immigrates to Canada with her 4 surviving children and marries a widowed Ottawa Valley farmer with two children of his own.

This is my paternal grandmother's story RE-IMAGINED lovingly by me.

To post I have to ask you read from #1 and thence backwards to the top of the page.

Hope there isn't Word protocol stuck between the lines now.

ko1

This is my paternal grandmother's story RE-IMAGINED lovingly by me.

To post I have to ask you read from #1 and thence backwards to the top of the page.

Hope there isn't Word protocol stuck between the lines now.

ko1

Saturday, February 7, 2009

Sunday, September 23, 2007

#2 Banbury Oxfordshire Spring 1871 Market Day

Banbury Oxfordshire

Spring 1871

Market Day

“Sarah Mother told you. You must hold my hand. If you let go one more time I’ll takeyou home.”

‘Yes Annie.’

I’m sure she won’t take me home. We haven’t done Mother’s shopping yet and

she hasn’t seen any boys her age yet. I love going to the Market with Annie. Annie

knows the names of everything and never makes me feel silly for asking. When I go

with Mary she just tells me I’m too young to know all that she knows.

The smells of the fresh bread, the bleating of the lambs, the calls of the hawkers

selling fabric, hats, baskets and my favourite sweetmeats. Mother can’t keep up with

the baking on Market Day because of the extra travelers who’ll stop at our inn for a

meal. Father says we can learn many things in the market that we can’t learn at home.

Mary says three Collins sisters is one Collins sister too many to go shopping

together. She says she’d rather stay home and help Mother. I hate it when she acts

‘the good daughter’. It’s so much nicer when Mary’s naughty and Annie and I are the

good ones.Father says people come here from three counties to shop on Market Day.

“Sarah mind the horse droppings. You insisted on wearing your Sunday best.

You must be careful. Auntie Dinah won’t be happy to wash your pinnie again before

Sunday.”

“Yes Annie.”

‘Lift your skirts.”

“Father says Auntie Dinah is a spinster. Father says the Smallpox scared off

all the suitors. Are you afraid of the Smallpox Annie?”

“Of course I’m afraid of the Smallpox. Look what it did to poor Auntie

Dinah’s face.”

I love Auntie Dinah and I’m glad she came to visit. She is Mother’s youngest

sister. She is kind and firm all at once. Dame Bennett could learn a lesson from Aunt

Dinah. Dame Bennett has a stick especially for children who cannot say their sums. My

sister Mary got the stick because she couldn’t add six plus eighteen. Even though

Mary isn't my favourite sister I didn't like her getting the stick. I cried when Dame

caned Mary but I didn’t let Dame see. Dame sent Mary home to Father when Mary stuck

her tongue out at her. Father doesn’t believe hitting children makes them learn. He

sent a letter to Dame Bennett in his best hand. It said Dame Bennett wasn’t to cane

any of his precious children. Simply send them home to him to punish. That night Mary

did many sums after chores but after our chores Annie and I got to sit in our beds

and read. Mary said she didn’t care but I felt her shaking when she got in bed and I

know she was crying.

“Mind your pinnie on that sheep stall. Those lambs have been sucking the

wood.”

“Yes Annie.”

I’m wearing my white pinnie and Annie let me wear her hair ribbon that

matches my blue dress. Mary says that ribbons are for babies but she won’t give me

her old ribbons. She hoards them in her box and says for me not to touch them. My

boots are black hand-me-downs from Mary and Father shined them for me last night.

When Father shines our boots they look like new. He says it’s the spit he uses at the

end. Father has the best spit. Father kissed us both said we are very smartly dressed

and he is proud of us.

“Annie did you see Mary making faces at us when we left?”

‘Yes Sarah I did. I don't care if but she is at home and

thinks herself clever for getting Mother and Father all to herself because we are at

the market just the two of us having an adventure. “

“I’d rather spend time with you Annie. You don’t boss me the

way Mary does.”

Annie squeezes my hand, “You’re my favourite little sister. I’ll bet you’d like to go

down one more aisle of animals before we go around Banbury Cross to the food stalls”

“Oh do let’s go down one more aisle. I love the baby animals.”

“Silly goose .You know they’ll all be eaten anyway.”

“Why do you tell me that? I hate knowing that.”

Sometimes Annie can act too grown up. I know she’s going to preach to me

about how ‘God gives us the animals to our use'. And she does.

I answer, “God should not make them so beautiful.”

The lamb is imploring me with her dark eyes to save her. I can just reach her soft black nose and scratch it. She nuzzles my hand. I’ll never eat lamb again.

“Sarah get your hand out of there. What if it bites??

“She won’t bite. Animals like me. You’ve heard the horses nicker when I go

in the stable.”

“That’s because you always take them an old carrot or a shriveled up apple.

Father calls that ‘belly-love.”

That’s not true. The horses really like me. I can go in their stalls

while the groom is brushing them and they lower their velvet noses for a pat and

snuffle their warm breath in my palm even when I don’t give them a treat.

I can see some of the neighbour boys skylarking about the cattle pens. They

are walking the board fences like circus tightrope walkers. I watch Annie as the boys

watch her. Annie holds her head high and pretends not to see them. Since she has

turned fourteen and pins her hair up she says she must act ‘a lady’. Mother told her

fathers are watching her to see if she’s enough of a lady to marry their sons. So I

hold my head up like Annie and when I stumble over my own feet and fall into the

fence I decide I’m not ready to act ‘a lady’.I regain my footing but now Annie’s got

the giggles and we can barely walk for laughing.

“Am I really that funny?”

“Little sister you are funny and sweet. I hope I have a little girl as sweet

as you someday.”

“Annie are you going to get married and move away?”

“Move away? Now where did that question come from?”

“Mother told me Granny Bryer was sad when she married Father and moved to

Towcester and that was only seven miles away.”

“Mother tells altogether too many sad stories.”

“Well I won’t ever get married but if I do I’ll live right here at The Bear with

Mother and Father.”

“I’ll get married one day but I promise I’ll never move far away.”

“Promise Annie. Cross you heart and hope to die.”

“Promise,” says Annie as she crosses her heart and points heavenward.

“Who will you marry?”

“I don’t know but Father says it will have to be a good marriage.”

“What’s a good marriage? One like our Mother and Father’s?”

Annie hesitates just a moment, “Yes like Mother and Father.

A good marriage is based on love. But Father says a man must also prove he can keep a

wife if they are to marry one of his daughters. A man who has a trade.”

“You mean they trade you for something else?”

“Not that kind of trade, silly. A trade is being a blacksmith or a carpenter.”

Father was a blacksmith like his brothers and Grandpa Collins until his hip

was badly broken. He was shoeing a skittish mare when she reared and came down hard.

Father has a big limp. Father says the mare was not to blame, that owner had

mistreated her and made her skittish. That’s what I like about Father. He’s kind to

horses just like me.

“Sarah can you hear the canaries? See those yellow birds in cages. Aren’t

they beautiful?”

“Why are they in cages? I don’t like cages.”

“You can buy them for a pet and take them home in the cage.”

”Can you let them out of the cage when you get them home?”

“No they’d fly away. You keep them in the cage and they’ll sing for you every

day.”

“I’d never sing if I were in a cage. If I had all the pounds in Banbury I’d buy

all the canaries and let them loose.”

“Sarah if you had all the pounds in Banbury you’d spend them on sweetmeats and

books.”

Maybe Annie is right about the sweetmeats and books. I’m

reading ‘Alice in Wonderland’. I love the part where she gets really big. I’d like to

be bigger than Mary. I might buy just one canary and set it free. My canary would

sing outside my bedroom window every morning at dawn just to reward me for freeing

it. No, that’s not a good idea. Mary and I share the bed beside the window and she

doesn’t like to wake up early. Mary makes me get out of bed first to get our morning

wash water because I’m the youngest. I know. I’ll train my canary to sing only at

teatime.

“This is the end of the livestock stalls. I’m glad the pigs were last. I cannot bear

the smell, ”Annie sniffs into her favourite lace hankie holding it against her

pointed nose. Mother says she has Granny Collins’ nose. A nose for gossip.

“Sarah take my hand. We’ll go down the next aisle to the

baker’s. We need to get the bread and buns. Father said to be back in an hour and

Mary will make sure he knows when that hour is up.”

“Yes Annie. I’m going to buy Mother a Banbury bun. They’re her favourite.”

Mother has been smiling more since we moved to The Bear and not lying in bed all

the day. She was always sad and almost always in bed when we lived in

Leighton-Buzzard at The Greyhound. Father calls her sad days ‘remembering George

days’. It’s because my only brother George died when he was a baby before I was born.

Mary says I can’t miss someone who died before I was born. She says only she and

Annie can miss him properly. Just because I didn’t know him doesn’t mean I didn’t

want to. When Mother’s having her sad days and doesn’t hear me I tell Father that

George is listening to me instead. Father says George is our special angel. That’s

another reason I like Father. He believes in angels.

“Sarah please walk faster. I’m hot and these bonnet ribbons feel like they are

cutting my head from my neck.”

We’re passing the first baker’s stall and everything looks

delicious. I see Banbury Cakes in rows and lovely smelling bread and buns. But Annie

has my hand and rushes us on, intent on going to Baker Jones stall.

“Annie you love wearing that bonnet. I saw you look at yourself in the hall mirror

and smile.”

“You did not Sarah Collins. The vicar says that vanity is a sin and I am not a

sinner.”

I did see Annie looking in the mirror and she knows it. Mother hung it high so that

we wouldn’t be tempted to gaze at ourselves. I saw Annie take a stool from the pub

and kneel on it to see in the mirror. I saw her from the stairway landing. She even

pinched her cheeks to make them pink. When I tried it I got red marks like midge

bites. I’ll say a prayer for Annie’s vanity at Matins this Sunday. Annie is my

prettiest sister. Her hair’s the colour of a copper penny and it’s ever so curly. My

hair is black and too shiny and won’t stay in its pins. Maybe if I got some vanity my

hair would be like Annie’s and the cheek pinching would work.

“Here’s the stall with the best Banbury Cakes. Don’t they look wonderful?” Annie

said as she bobbed and blushed at Baker Jones.

“Now where did I put Mother’s list?” she said shaking her head.

“Now you’re the silly goose. Mother gave me the list. It’s here in my pinnie pocket.”

On the way home from Market Annie and I carry our cloth bags carefully out in front

of us to avoid squashing the buns. Even though we are close to the inn I have to

put my bag down to rest my aching arms. Annie says keep walking, as she knows by the

clock tower that our hour is almost up. Around the corner of the last stall comes

Martin Jones, Baker Jones' son and Annie stops walking causing me to bump into her

and we both drop our bags. Martin stops and helps us put the buns back in the bags.

Lucky for us we were on a grassy bit or we would have dirty buns for the travellers’

tea and Mary would have been happy to see us in trouble.

Martin whispered something in Annie’s ear and she blushed

from her neck to her cheeks that saem blush she had when our cousins Walter and

George and Aunt Mary Ives came to pay a call. That day we three girls were sitting in

the parlour all in a row, only speaking when spoken to, our hands folded perfectly

still in our laps. Walter was sitting on the loveseat next to Annie. I was thinking

how proud Father and Mother must be of us and maybe we’d get an extra sweetmeat when

I saw Walter pass something to Annie.

Without warning Annie turned a thousand shades of crimson

and fell on the floor right at my feet. Mother was appalled and ran for the smelling

salts. Father laughed that it was Walter making cow eyes at Annie that made her

faint.

Annie didn’t faint. She dropped what Walter passed to her

and didn’t want anyone to see it. She had his love letter in the sleeve of her

nightdress when we knelt for our prayers that night. She secretly showed me the edge

of it and told me that he’s being apprenticed to a carpenter in Banbury. When I heard

that I was happy because if Annie marries Walter she’ll still be close by. She

crossed her heart and hoped to die that she wouldn’t move far away. No one would dare

to break that vow.

I’m not telling Mother and I’m not telling Father and I am

certainly not telling bossy Mary. That’s what I like about eldest sisters. They trust

you with their secrets.

Tuesday, September 18, 2007

# 8 NEW GRIMSBURY, APRIL 1875

New Grimsbury Warkworth

April 1875

April 18, 1875

Dearest Diary,

The spring sun is streaming through our leaded glass

windows making diamonds of red and gold on the pale walls of my bedroom. Mopey Mary

has finally gone downstairs and I can write without her sighing and whinging about

writing and reading being a waste of time and I can write.

I hope next week Saturday we’ll have good weather as

my best sister Annie’s getting married.

I can hear laughter from the yard and I clamber onto

the windowseat to spy on the merriment. I scrunch up close to the farthest east

side of the window and I can just see into our yard. Annie and our char Ellen are

carrying a large wooden washtub. The sloshing water causes them to crash into the

apple tree. They stop in their labours and lean against the tree for support. I

can hear their exaggerated laughter. Annie calls out, 'Just a few miles more miles Mr

Livingstone' and they surge forward again. They gain the stoop steps and heave the

washtub onto the top one. This motion shoves the water forward again and more spills

down the side of the washtub and onto the steps, the soap making a frothy pattern.

Now Annie cries out,'The falls! I've discovered Victoria Falls.

They both laugh again.

I see Ellen coming from the house again. This time she's carrying a large pail

of water. When she reaches Annie's station she manoeuvres around her and slaps the

pail down beside the washtub. Now they engage in a kind of laundry dance with a

threesome of Annie, Ellen and a dripping soapy tablecloth as their partner.

First they wrestle it out of the foamy water, each taking

an end and twisting in opposite directions until they can twist no more. The dance

continues with Annie and Ellen each twisting in the opposing direction again until

sudsy froth releases on the ground. It's winter in April.

It's Mother's finest linen and Annie wants to use

it for the family table at the wedding dinner. Annie plunges the sodden cloth into

the pail of clear water loosening it as she goes. Out from the water it comes and

the laundry dance starts again, rinsing and wringing until the tablecloth is free of

suds.

'Well done Miss,' says Ellen glad to have Annie's help.

Now they each take an end and walk with it stretched out between them and lay it,

smoothing out the creases on a clean patch of grass.

'Sun'll bleach out stains and when it's got a bit of

damp left I'll heat the flatiron and press the beejeebers out of it. It'll look

luvely for t' weddin' dinner,' says Ellen.

For one minute I see Annie smiling at Ellen and then

I see Annie as if in slow motion look towards the flower garden, throw up her hands

to her mouth and run towards the house.

Oh dear, the kitchen door has just slammed and I can hear

Annie sobbing. What can have happened?

I will finish this later.

S.C.

I just get to the kitchen when Annie throws herself into my

arms.

“The daffodils are finished. My wedding procession

is ruined. There won’t be a single daffodil to carry next week. I don’t care if I

ever get married.”

This is not like my sweet sister. For a moment I think

she’s turned into Mary. Then I see a great glowing tear run down her flushed cheek

and I hug her closer.

“Sarah what am I to do?”

I walk through the garden in my mind.

“I know just the thing. Tulips. Romantic too. Two

lips.”

“Sarah you know just the things to say to make good

from bad but the tulips are already opening.”

“I was chasing Puss away from a baby sparrow and saw the

tulips on the shady north side of the garden. They haven’t even opened yet. They’re

yellow aren’t they? “

“Yes and they will look lovely with your blue dress. I have

decided I cannot get married without you beside me.”

“But Annie you’ve already asked your best friend to

stand with you.”

“I know and I know you’re too young to sign but I

know you can carry my train and be in the procession. You already have your blue silk

that makes your eyes shine. Wear that and I’ll carry the yellow tulips and all will

be wonderful.”

“Mary will be jealous.”

“I’ve asked her to do a poetry reading at the dinner

and she is consumed with rehearsing it so she’ll be fine. It’s Mrs. Barrett’s ‘How do

I love thee?’. It was Mother’s favourite. Having it read will be like having part of

Mother with us.”

“Do you really think Mary will be fine? She can be

devious. Just when you think she’s happy…” and I pull my dress sleeve up to show

Annie a yellowing bruise.

“I’m thinking only good thoughts for my day Sarah

and I want you to do so as well. Please do this for me. Don’t speak harshly of Mary.

It does upset me so. Our dear Mother has been on my mind all month long. How she

would have enjoyed the planning and the baking and all that goes with a wedding.”

I myself am not so sure. Mother could sometimes be happy but

I have such a strong memory of her long face. I feel a little quiver run up my back.

‘Someone is walking on your grave’, Gran Collins would say.

“Yes of course Annie. I won’t spoil your wedding day

with my worries.”

“Don’t even say ‘worries’ please,” Annie says and stamps her

foot. I jump in mock fear and we both fall over on the settee laughing.

We hear Mary comes in the kitchen. She looks through the

pass through at us sprawled on the settee as if we have two heads. She’s been waiting

for the paste to dry on our one silver tureen so that she could buff it to a soft

shine. She is at least helping with the preparations. She is being so helpful that it

makes me wary. Who will she pounce on next?

Mary picks up the tureen and turns it around slowly in her

hands. Without looking up she says,

“I saw Mrs. Garrett limping away from the Post Office. She

says when her bones act up it’s going to rain for a month.”

April 18,1875

Dearest Diary,

That Mary. She knows how to upset Annie. On the very morning

while Rev. Ruston was publishing the banns of marriage for the third consecutive

Sunday and with Annie and Walter sitting right in Christ Church in the same pew, Mary

managed a loud coughing fit. Mary was so loud that Father asked Mary, with that voice

you never want to hear Father using, to leave the church and wait for him in the

lychgate.

I’m glad Father didn’t tell me to go there. I would have to

have misbehaved. I always walk through the lychgate as fast as I can. That’s where

they used to lay the shrouded corpses when they weren't buried in a coffin.

I shouldn’t be thinking such thoughts just before

Annie’s wedding so I promise that’s the last one.

I’m so excited. I’m going to be carrying Annie’s

train in the procession. I’ll wear my blue frock and I think Annie will have her best

friend and matron of honour, also named Annie, put my hair up. It’s my first time

ever with my hair up. All the family will see that I am not just ‘little Sarah’

anymore.

Annie has chosen a simple white gown much like the one Queen

Victoria wore when she married her beloved Albert. It has a frothy veil that will let

her glorious copper curls shine through. I heard Mary chant at the dressmakers,

‘Married in white, you'll have chosen all right.

Married in grey, you'll go far away.

Married in black, you'll wish yourself back.

Married in red, you’ll wish yourself dead.

Married in blue, you'll always be true.

Married in pearl, you’ll live in a whirl.

Married in green, ashamed to be seen,

Married in yellow, ashamed of the fellow.

Married in brown, you’ll live out of town.

Married in pink, your spirits will sink.’

I wonder if she’d have been so quick to sing out if

Annie had chosen green. If Annie had chosen brown I would have wanted to wear black

because without my sweet sister Annie near me I’d want to die. Just one more bad

thought. Though Annie asked me not to speak harshly of Mary I can still tell you

dearest Diary. When Annie was so upset about the daffodils I saw a familiar look in

Mary’s eyes. It’s the look she gets when she’s planning mischief. I didn’t tell Annie

but I’ll be watching Mary just in case.

Yours in hope,

Sarah A. G. Collins

.

# 7 New Grimsbury,Warkworth January 25, 1875.

New Grimsbury

Warkworth

England

January 25, 1875

“First we arrange our chairs so we have the best light. Sarah

I’ll need your help.”

“Yes Gran. Where would you like your chair?”

“Beside the window and bring over the reading lamp and my

sewing basket as well, please. My old eyes just don’t see as well as

they used to. Don’t forget your own needle case.”

I half drag half carry Gran’s chair for her and

position it as she requests. It isn’t quite right so we try it again. Success. Next

my chair goes close to the same spot so that I will have a clear

view of her fingers and all she does. I am so excited to be starting

on real embroidery with my own needle case and all. Having

Gran all to myself is the second treat. She tells good tales about

when she was a girl and she sometimes tells tales about when my

own Father was a boy.

Gran holds my one elbow and grips the arm of the

easy chair with her other hand. She lowers herself into the easy chair. Her

mouth makes a puffy sound as her bottom drops the last few inches onto the seat

cushion.

“I never know if I’m going to fall in and I wonder if I’ll ever

get out of the chair again,” she laughs.

"Oh Gran you know I’m here to help you.”

“Sarah you are a gem indeed. Now sit down and hold your

hands out front of you at the level of your waist. Can you see your

right hand with good light?”

“A little shadowy. Shall I turn my chair a little?”

“Exactly right. Now is that better?”

I nod yes and Gran reaches into her wicker basket and brings

out the most beautiful napkin I have ever seen. It’s white and has

white embroidered initials and has holes with thick even stitches of

embroidery around them . She hands it me. I accept it reverently

and hold it on the flat of my two hands.

“Oh Gran I don’t think I can do this. It looks very

difficult.”

“I wouldn’t expect you to do this straightaway

Sarah. It’s called cutwork and it takes a practised hand. I wanted to show you

what you can strive for. If you don’t have a goal then you can

never reach it.”

I nod yes again but truly wonder if I will ever embroider this

well. As if Gran has read my mind she turns to her basket

again, puts away the cutwork and brings out two men’s hankies

well worn and washed to softness. They looks like Father’s.

“Time for you to get started. Would you like to use

your Father’s handkerchief as your first practice piece? It’s soft and will

be easy on your fingers. I filched two from the laundry as Ellen

was taking it upstairs yesterday. Ellen wasn’t sure I should take it

as she feels, as most help does, that she is responsible for missing

items. I told her, ‘If my son gives you any cause please tell him

to speak to me.’ She seemed relieved at that.”

Gran took one of the hankies and pulled her

embroidery hoop from her basket and proceeded to force the fabric taut between the

two hoops. She motioned to me to do the same. I struggled to do

it as quickly as Gran did and failed. There was a big fold right

across the middle.

“Sarah. Lesson number one. Do not rush.”

“Yes Gran.”

The second try was the charm. The next hour anyone

coming into our parlour would have seen two heads bent over one task.

One snowy and with the slightest tremor, the other shining darkly

looking upwards every few moments to the snowy one for

guidance.

"I’m lucky to have you to teach me this Gran. I

really think I can do it."

“I’m happy to be with you Sarah. We have a lot of

time to make up. At your age I was helping my mother sew the family’s clothing. We

sewed the winter clothes in the summer and we sewed the summer clothes in the winter.

In between we mended. I think you will sew a fine seam. Not everyone has the means to

buy their clothing from tailors and dressmakers.”

“I though we were just going to embroider.”

Mother always sewed our clothes on her Singer Sewing

Machine but she mended our clothes by hand. Maybe Gran is as old fashioned as Mary

says. Father bought Mother the sewing machine in Banbury and it was the first one on

our street. Mother was proud of it and many of the neighbour ladies came in to

see it. I am feeling a little scrappy but it is not proper to correct your elders. I

bite my tongue.

“Your dear Mother knew how to sew by hand but your

Father provided the sewing machine so she never had to. But Sarah there

may come a day when your life is different, a time when you may have to live by your

wits. Any skills you learn can be put into good use if the future does not bring you

a good wage earning husband. Think of your Aunt Mary. Her husband died at a young age

and she had to support Walter and his brother on her earnings until they could work

too. I was right to teach her to cook and sew. Now she runs the Soup Kitchen in West

Ham.”

I want to tell Gran that I won’t marry unless I madly adore my husband to be,

like Annie and Walter, and that Father has instructed we three girls that no suitor

need come calling if he can’t support us properly. I hold my tongue. I love my Gran

and I don’t want a foolish spat to spoil the day.

Gran reached back into my needlecas. This time it

yielded a tiny pair of silver-coloured scissors. So tiny what could they be used

for? Gran turned her work over, took three tiny stitches on the wrong side of her

work and then snipped the embroidery floss close to the surface of the hankie. You

could barely see where she took those last three stitches. I shook my head. So much

for me to learn.

“I think Father will be pleased and surprised to see his initial

on his hankies. Just like the shops in the High Street sell.”

“Not half as pleased as you will be to see the smile on his

face and his knowing that you made one for him,” Gran beamed.

I flushed in anticipation of the big day.

“Gran when you said Mother could sew, did she ever hand

sew any clothes for us?’

“I’ve never seen any except the baby layettes.”

“What’s a 'layette'?”

Gran delights in giving me new words. This one wasn’t an English sounding

one. Layette?

“A layette is a complete set of clothing for a

newborn baby. Sounds like a French word to me but I don’t know how it came

across the Channel to England. I really don’t.”

“Did Mother sew a 'layette' for me?”

“My Sarah. You are full of questions. Does your mind

ever sleep?”

I nod yesbut think 'Is Gran trying to avoid my

question?' Often my questions about our Mother go unanswered. Only Annie listens to

my questions and gives me answers. I decide to try again.

“Did she Gran?”

“Oh Sarah. After all the babies your Mother loved

and lost she quit making layettes. There were enough leftovers by the

time you came along to last you until you were well out of

nappies.”

“What do your mean by ‘all the babies’? I only know

about losing George. “

Before Gran or I could take another stitch or say

another word Mary and Annie burst into the room. Their coats were powdered with snow.

“It’s snowing. Sarah come outside with us. It’s lovely. It’s

like the baker has sprinkled the town in sugar.”

# 6 New Grimsbury,Warkworth January 1875

New Grimsbury

Warkworth

England

January 15,1875

Dearest diary,

It’s a glorious new year and my New Year’s resolution

is to write in this diary more often. I have been a disappointing

diarist (Gran taught me that word) but my late dear mother’s words ringing in my ear, ‘ Sarah

you speak enough for two children. Write some in a diary.’ So I

will.

This has been the best Christmas since our Mother died.

Partly it was because my Gran Collins has moved from Church

Stowe to live with us. Mary is always on her best behaviour when

Gran is here. Gran loves Christmas. Mother always said Gran has a

sharp nose for gossip. I think Gran has a sharp nose and eyes for

nasty sisters who pinch. Mary always behaves when Gran is about.

Gran bought us each a gift this Christmas though I suspect it

was Father who went to the shops. Gran is quite frail. She will be

seventy-two at her next birthday.

Gran gave Father a new red muffler. She said he needs

brightening up. Father laughed and said, ‘Are you still trying to

dress me my age?’ It’s hard to imagine Father a small boy at

Gran’s knee. Even though he has a limp from blacksmithing and

hasn’t used a hammer in years he still is big and strong enough to

pick me up.

Gran gave Annie a lovely cream ware pitcher that Gran used

when she was a young bride. This gift’s significance will be

explained later dearest diary. The pitcher has red roses on the

sides. Annie insisted we use it at our Christmas feast.

Mary received three lace trimmed hankies each with a

different flower embroidered on the corner and the letter ‘M’ on

each hankie as well. None of my hankies have lace or embroidery.

Mary waved them in front of my face until I though I would faint

from envy. That’s another sin the vicar likes to sermonize on at

Matins. So I just turned my head until Gran said, ’I put that

embroidery on those hankies and I know how to take it off too.”

You don’t want our Gran angry with you. No you don’t. Mary

squeezed a few crocodile tears out for Gran. Hah.

Aunt Mary Ives and cousin Walter arrived on Christmas just

in time for midnight service at All Saints. We had to take two

buggies as there were so many of us. Annie picked me to go with

she and Walter. We three bundled up under one carriage blanket. I

can always count on my sister to include me in her plans, even

with Walter.

Aunt Mary is a widow but she is very jolly and she knows a

great number of parlour games. We played ‘Do you love your

neighbour?’ until we were all panting like Gran’s silly dog. He’s

an English bulldog and he is the only thing I don’t like about Gran.

He snorts and snuffles as if he has catarrh.

Our family had never played ‘Do you love your neighbour’

before but we soon learned to scramble for the last seat to prevent

ourselves from being ‘it’. Walter always managed to have Annie

sitting on his knee as if he got the seat and she tried to sit on it at

the same time. I know he pulled her on his lap every time. She

could hardly sleep that night. Something exciting was going to

happen and I knew what it was. Gran calls that having a

premonition.

You will just have to wait a little longer dearest diary and

you shall know as well.

Walter has completed his apprenticeship. He has secured a

position with the Carpenters and Joiners Guild at Banbury. Annie

is so happy.

But that is not the biggest news. I’ve saved the biggest

news for last. Have you guessed it dearest diary?

Walter asked Father for Annie’s a hand in marriage. Walter

asked at the dinner table on Christmas Day. Father jumped up and

clapped Walter on the back and kissed Annie on the cheek. She

wasn’t half blushing. Then Father raised his glass of ale for a

toast, ‘Sister let’s all raise our glasses. Now my nephew will be

my son and my daughter will be my niece. Here’s to their every

happiness.’ We all joined in the ‘huzzahs’.

Your true friend,

Sarah A G Collins

P.S. I almost for got to tell you the gift Gran Collins gave me for

Christmas. It’s a needle case with a pink chintz cover and inside

are all sizes of needles and a pair of tiny scissors and what

Gran calls an embroidery hoop. Gran promised to teach me to

embroider. I know in my heart Gran will be a good instructor. I

plan on embroidering all my own hankies. I’ll show that Mary.

# 5 NEW GRIMSBURY WARKWORTH JULY 1874

New Grimsbury,

Warkworth, Northamptonshire

July 6,1874

“Sarah as it‘s your twelfth birthday what would you

like to do as a special treat?” asks Father as we finish

our evening meal.

“Can we go to the band concert at Cherwell River

Park?”

“I was hoping you would ask that,” beams Father.

“Can we walk to the park please? It’s such a warm

night and it is my birthday.”

“Mother do you think you would feel up to coming

with us?”

Gran Collins shakes her head,

“Thank you for asking but no is my answer. I’ve had

enough excitement today what with Sarah’s birthday and

the singing and the gift opening. You go along and enjoy

the evening.”

“I’ll stay with Gran. You know I don’t like the music

and I’d rather not go,” says Mary.

“That is kind of you Mary,” says Father.

I hold my tongue. Father always thinks the best of

everyone. I want to say, ‘Is there anything you do like to

do Mary, besides pinching me behind Gran’s back?’

Soon Father, Annie and I are walking to the park as

it is just across the bridge from New Grimsbury in East

Banbury. I’m carrying my new mauve parasol. I practice

twirling it like a saw a lady on the High Street do last week.

The parasol flies out of my hands and into the road.

“Father. Father. My parasol.”

A horse and cart is lumbering our way and I’m afraid

my parasol will go under its wheels.

Father dashes into the road, scoops up the parasol and

delivers it to me with a deep bow. I love my Father so

much. Other Fathers might have scolded.

It is a soft velvety evening. Father is humming and

imitating the instruments in a military band. "Pa bump

bump. Pa bump bump. Ta rum rum. Ba bump."

He is in high spirits. We have to step lively to keep in

pace with his long strides all down Middleton Road. The roses are

blooming on the cottages along the way and patrons are sitting outdoors having pints

of ale The Bell and The Cricketeers by the bridge. I can’t think of a fairer place in

all the world.

As we cross the Cherwell we can hear the music

floating on the air all the way from the park. Father says he

is proud to have tow such delightful young ladies on either arm

and he must be the envy of all the young men in Banbury. He says it could only be

nicer if Mary were with us.

I snort and Father looks down at me.

"Sorry Father. I must have dust in my nose."

It would be romantic to pretend we are walking with a

sweetheart as the scent of blooming roses wafts up to us.

But then the band strikes up ‘Rule Britannia’. Soon we three link arms and are half

walking, half marching towards the bandstand.

Father says, ‘Pick up your feet men. You’ll be drummed out

of your battalion if you lollygag.’

I wonder if anyone said that to Florence Nightingale?

We see young boys using sticks for guns and playing

at being Prussian and French soldiers. Father says that war was in a faraway country

but it will continue to touchus in many ways. I don’t like war so I don’t listen. I

would never marry a soldier. I just sing a merry tune in my head.

What a surprise. It’s cousin Walter Ives strolling in the

park with a group of young men his age.He breaks away from them impervious to their

taunts and comes running to Annie’s side. He barely tips his hat to Father and I as

he is intent on greeting Annie.

Walter asks if he may join us and Annie says, “Yes,

But isn’t this park a long walk from your boarding house?”

Walter doesn’t seem tired and mysteriously Annie

doesn’t seem surprised to see him.

I’m certain Annie and Walter are sweet on each other. But

I’m not worried as his move back to his mother’s house, our Aunt Mary’s, in West Ham

when he completes his apprenticeship will remove him from Annie’s list of prospective

suitors. Annie has promised me she will not marry and move away. West Ham is far away

on the edge of London. I wonder should I tell him so? I decide no. That’s

just as well as I can’t get an opportunity to speak with him alone as Annie is both

hanging on his every word and off his arm.

After the concert fireflies dart in and out of the bushes

around the edge of the park. Mother once told me fireflies are memories that you

forget. Father buys us each ice creams from the vendor. We have a choice of lemon or

strawberry. I pick lemon. It is heavenly. I should like to eat it every day. Mary

will be jealous that we had ice cream and she didn’t. If it was the other way around

she would torture me with a description of how cool and utterly delicious it was. I

will not stoop to teasing her. I’m twelve now and it’s not ladylike.

We walk out the east gate of the park and to the

bridge. This is as far as Walter can walk with us as he has

to walk back to the far side of Banbury to his boarding

house . He rises with the sun each morning to work with

the Master Carpenter. Since Walter moved from West Ham

to Banbury Walter is able to call at our home once a month

or so and sometimes takes a meal with us.

Annie calls, “Goodbye Walter.”

“Goodbye Annie. Goodbye Uncle. Goodbye Sarah and

Happy Birthday again.”

Annie barely says a word all the way home to 44

Middleton Road. I wonder if she and Walter have plans that

I don’t know about.

July 6, 1874

Dearest diary,

It was my birthday today and I am twelve years old.

Our Mother has been dead for two years. I do wish I could

talk to her about my life. Perhaps she can read you, dearest diary, from heaven.

That might seem foolish to anyone else who might read

this diary but no one can understand how much a girl can

miss her mother.

Sometimes I can remember her face and sometimes

it’s just a shape of a woman I see. I often ask Father to see the miniature he has of

her in his watchcase but it’s so small it could be anyone’s

mother.

I do have Mother’s madras shawl. It’s soft wool in colours of red and gold. It was

the last gift Father brought her before she died. For a long time it held her

scent; like lilacs and sun all mixed together. Now it just smells of me. I wrap it

around me when I feel sad and missing her. I wore it to bed one night and Mary said,

‘Take that shawl off. You’re just trying to make me jealous.’

At the park tonight we saw lightning bugs darting about the

bushes. Gran Collins told me lightning bugs are the memories of lost children and

they come back to remind their parents. Maybe George was with us tonight. I wonder if

Father saw them.

Mary has Mother’s diary. I let Mary see and even

touch the shawl but Mary won’t let Annie or I read the diary. There are so many

things that I can’t remember about my mother and reading her own words and seeing her

handwriting might bring her back to my mind. Someday when Mary is not at home I plan

to find where Mary hides the dairy and read it cover to cover. I’ll tell her I did it

too and see how she likes it.

Annie shared her ice cream with Walter tonight. She

says she wants to keep her figure and eating ice cream makes you heavy. Annie could

eat ice cream all day and all night as she is tiny like Mother and Gran Collins. I

think she just wanted to share with Walter.

Father says every young lady should be aware of

her prospects. Mine are dismal. I am still flat-chested and I

have a strong nose. I still have that kind of hair that will not

stay in its pins. Annie says that is it lovely and shiny. She

doesn’t have to worry about anything as she has curly

coppery hair that looks stays in pins and her nose is tiny

like Gran Collins.

Oh ! I have only just now figured out why Annie

wasn’t surprised to see Walter. She remarked to me last

week that she saw a poster pasted on the wall of The

Cricketeers advertising a band playing at Cherwell River

Park on the same day as my birthday. Annie knows how

much I love music and that Father gives us a special treat

on our birthdays. Hmmm? Did she tell me about the concert

so that she could tell Walter we would probably be at the

concert?

My question for you tonight, dearest diary, and this

is very important,

‘Do you think Annie will move to West Ham and marry

Walter? In spite of her promise to me?’

Your true friend,

S A G Collins

Sunday, September 9, 2007

#4 OPEONGO LINE 1934 NEW GRIMSBURY 1873

Opeongo Line

Clontarf, Renfrew County

Ontario

Fall 1934

Peg and Morgan burst in the door. Peg drags a potato sack across

the floor. Their cheeks are as red as the apples that spill from the sack.

Peg’s smile tells me that she is so proud to have been the one to carry

the apples to me. I wonder how bruised they are after their eventful

entrance across the wooden floor. No matter.

“Thank you Peg and you Morgan. Don’t hang back boy. Did you

help pick these beauties?”

“Yes Grandma right off the ground. They’re windfalls. Mamma

didn’t want them to go to waste.”

“Your Mother is a wonder. Five children and a babe in arms and

she still finds time to send you two out for apples for Mick and I.” I

wince inwardly as I admit to myself that I didn’t always hold her in such

high regard.

"Where is Grandad?” asks Morgan.

“Oh likely out telling your father the proper way to farm.”

Morgan is sniffing around the cupboard looking for anything

edible. Even with the meals Laura puts on Morgan is ever hungry, his

arms escaping his shirtsleeves. What will he eat like when he gains his

teen years? I open the bureau drawer and both Morgan and Peg’s eyes

light up. It’s the drawer with the peppermint.

Sucking loudly in unison they’re soon out the door into what’s left

of an Indian Summer day. A gust of wind catches the door of the Little

House and bangs it back against the wall. Ever-thoughtful Peg runs back

to close it.

“Sorry Grandma,” and she’s off like a sprite.

Now what to do with these apples? Applesauce will go well with

Laura’s fresh bread and butter. Morgan does love his applesauce.

I pick up the reddest globe and polish it to gleaming on my apron. It’s

redolent of summer sun and the sharp scent takes me back to another

Fall day far in the past.

New Grimsbury

Warkworth.England

Fall 1873

The wind has been playing tag through the village for days

now. The leaves jump up hoyden-like as we turn the corner of the house

and head into the wind towards the garden shed. Aunt Dinah has sent

Annie and I to get baskets. The windfalls are too plentiful for our

neighbour to gather before worms or rot takes them. He offered our

family a basket for every two we gather.

“They’ll make good applesauce. Mind not to bring home any

wormy ones,” Aunt smiles her round face smile in anticipation of the

sweet treat ahead.

I love being chosen to go with Annie. She’ll be seventeen soon and

I worry she’ll marry Walter Ives and move away soon.

“Come little sister. I’ll race you to the shed.”

Annie’s still fun even though she’s almost grown up. She has

longer legs than me and easily beats me to the shed.

The Wisteria lies in wait hanging heavily from the shed. Its

loopy tendrils try to capture us. We’re too quick for it and dart safely

inside out of the cool wind. The dank coolness rises to greet us from the

dirt floor. The sun risks strangulation to send us a few tentative rays

through the massive foliage.

“What if the Wisteria grew so fast that it trapped us in here? It

would be like The Mill on the Floss. Father would have to come home to

hack us out with the kitchen knife.”

“Sarah it was a flooded river that trapped them not a Wisteria,”

Annie laughs.

I rush on ignoring her friendly rebuke.

“I would be Thomas as I haven’t grown into my woman’s body

yet. You would be Maggie because you have.”

“Oh I have, have I?”

“Yes and Father would be dispatched home and would wander the

streets calling our names by day and by night. His throat would grow

hoarse and still he’d keep walking and calling,” and I hold my hand over

my throat for emphasis.

“Really Sarah you are a bit overly dramatic.”

I shake my head and Annie smiles.

“The Wisteria is wrapped so tightly around our throats that we

can’t answer.”

“Stop now Sarah even I am starting to feel like the Princes in the

Tower.”

I think who’s being overly dramatic now?

If the postman goes by when Annie is expecting a letter from

Walter she weeps. Oh true love. I don’t want true love if it makes you

weep.

“Now where are those baskets? Mother always kept them near the

front wall.”

Mary, ever jealous of Annie and I, has taken to hiding Walter’s

letter if Annie isn’t home when the post comes. Annie seems to know

when there is a letter is in the house and she hounds Mary until she

releases her spoils.

Annie’s rummaging about for baskets has stirred up dust motes.

They glimmer in the few captive rays of sun. It’s quiet. No Mary bossing

me. No Father away on endless business trips. I like it here.

I stoop to pick up some fallen plant fames and I stack them neatly

on the dusty shelf beside the window. Next I spy a row of overturned

plant pots. I march them in a neat row along the window ledge. I catch

Annie’s bemused smile as she watches me from the back of the shed.

“Oh Sarah you are so like our Mother when you do that.”

“Like Mother?”

“Yes like Mother. She hated messes as much as she hated

surprises.”

“Was I a surprise? Being born a girl I mean?”

Annie motions me to the back of the shed where she dusts off a log

stump with her hand. She inspects the amount of dust on her hands and

then rubs her hands lightly together. She inspects them again. Satisfied

she sits on the stump and smiles at me. Such a warm smile.

“Bring over a chair, I mean a stump,” she laughs "and we‘ll have a

chat.”

“Will you tell me the story of the day I was born?”

“That same story again?” Annie teases.

“Yes please. I want to always remember it especially my naming

part.”

I find two stump candidates and vote for the smaller one. I roll it

end over end to where Annie has elected to sit. Now the dust motes are

Morris dancing.

To me Annie looks as regal as a queen on her throne and twice as

beautiful as our queen. Father calls Queen Victoria “that old black crow”

but I am Annie’s loyal subject ready to revere her every word.

”The day Sarah Ann Green Collins was born the sun was

shining. Aunt Sarah lived with us then. She was Granny Bryer's

eldest sister and she was over fifty years old even then.”

I wiggle on my stump hassock anticipating my favourite naming

part of the story. It‘s delicious.

“And then what happened?”

“Well we were in the garden behind The Bear Inn. Do you

remember The Bear Sarah?”

“Yes yes. But who was in the garden?”

“Well it wasn’t you silly. You weren’t born yet.”

Annie laughs everytime she tells this part of the story to me.

Sometimes Annie thinks she’s funny when she’s not.

“Who was it then?”

“Be patient little sister. Aunt Sarah had made a picnic under the

apple tree for Mary and I. We had our dolls outside with us and they

were having a tea party. Father told Aunt Sarah to keep us away

from the house that day."

“Why?”

“Mother was making the noises women make when they’re having

a baby and Father didn’t want us to hear.’

“What were the noises?”

“Well I can’t tell you now can I as I wasn’t near the house. You’ll

have to wait until you have your own babies to find out.’

“Not me. I don’t want to do something that makes me make noises

that children shouldn’t hear. “

Annie paused and smoothed her apron over her knees before she

realized she was transferring the dust from her hands to it.

“Now see what I’ve done.”

“Annie. Annie. More story. Please.”

“It was my turn on the swing. It was a good day for swinging

and I pumped the swing so high that I felt I could fly. Fly to India in a

hot air balloon.”

“Annie. What about my story?”

“Oh yes. I was swinging really high when Mary grabbed the

swing’s rope and I came about like a sail and collided with her.”

“Then what happened? Was I born yet?”

“Not yet. First I woke up with a headache and a big goose bump on

my forehead and Mary had an even bigger one.”

“Serves her right. She was yelling?”

“Mary was yelling.’ It was my turn’ and Father was standing over

me. He blocked the sun.”

“What did he say? What?”

“He said,’ Let’s get you two heathens cleaned up. You’ve a new

sister to meet.’ ”

“He called us heathens?’

“It means we weren’t acting ladylike.”

“Were you happy I was born?”

“Yes I wanted a sister. Mary was turning out to be nasty and I

was hoping for a new sister. I got my wish.”

“Were Mother and Father happy too?”

“Sarah. Mother and Father were still sad about George. Mother

never stopped being sad about George.”

“But they did love me didn’t they Annie?”

“Oh Sarah we all loved you. You had a face like a rosebud even if

your stinky nappies didn’t smell like roses,” Annie laughed.

“All babies have stinky nappies.”

“That’s true.”

“Tell me the naming part now. Please.”

Annie closed her eyes. Had she forgotten my favourite part?

“If you’ve forgotten it’s alright Annie. I think I can even tell it

myself. I’ve asked you to tell it so many times.”

“Would you like to give it a try Sarah?”

I straightened my back and lifted my chin as I stood up. This was

important. It was the first time I’d told my naming story myself.

“You and Mary and Father went upstairs to Mother’s room.”

“You forgot Aunt Sarah.”

“Oh yes and Aunt Sarah too. Was Mother awake?”

“Yes.”

“All stood by Mother’s bed except for you. You were hiding in

Aunt’s skirts. Mary scrambled over the bed to Mother and said she was

going to name the new baby.”

”That’s right Sarah. Keep going you’re doing a good job.”

“Then I think you said something…”

Now Annie stood up and struck a pose that any stage director

would be proud of. She raised her right hand as if pointing to God and

said and her most authoritative voice,

“She shall be Sarah Ann Green Collins.”

“I love this part.”

“You were swaddled in a pink blanket. Father picked you up from

Mother’s bed and put you in Aunt Sarah’s arms.”

“Was she happy?”

“Oh yes and proud too.”

“What did father say then?”

“I think that you know this part by heart Sarah.”

“I do. It’s my very favourite part. Father said, ‘A big name for a

little girl’”

Clontarf

1934

The sun went behind a cloud and I started at the sudden

darkness in the middle of a sunny day. I was trying to remember

something about that other Fall day so far in the past.

The sun went out and we stood with our arms around each other.

I remember crying. Why was I crying? Is there a piece of the story

missing?

I have an ache near my ribs again today. I rub it hard with my

knuckles. Doesn’t help. To the task at hand. Make the applesauce.

#3 1872 NewGrimsbury Warkworth Northants

New Grimsbury. Warkworth

Northamptonshire

January 1872

Annie, Mary and I have our eyes closed and we are walking

I know I must look at our Mother. I lift my head from

Annie’s back and open my one eye just a smidgen. I see Aunt

lighting candles and placing them at the head and foot of the casket.

Our Mother lies between them.

At least it looks like our Mother. She has the same small

hands that taught me to k1 purl 2 and clapped happily when I said

all my times tables correctly. She has the same dark shiny hair

parted in the middle with curls around her ears. She’s wearing our

Mother’s favourite blue dress. It has a wide lace collar with the

same edging that our Mother tatted. I don’t know if she has the

same blue eyes as Mother, as her eyes will always be closed. She

must be our Mother even though I don’t want her to be.

Aunt says our Mother’s spirit is in heaven but her body is

still here. It must be confusing to be dead; the being in two places at

once I mean.

Now we three sisters are lined up along the casket. Each of us

make praying hands.

Aunt says, “As soon as the neighbours see your father’s trap

pull in our yard they will come to pay their respects.’

Aunt has never spoken more seriously to us excepting the

day Mary put Puss in the well bucket. But she does look comical

stuffed into the stern black dress she wore at Grandma Bryer’s

funeral with her white nightcap. Aunt Dinah does love her sweets

just like me. She’s as round and jolly as Mother was thin and quiet

and I think she just hasn’t had time to dress her hair what with the

undertaker’s visit and taking care of us. I must bite my knuckles to

stifle a giggle.

Aunt continues, “You may use this quiet time to tell your

Mother your most tender thoughts. The house will be filled with

relatives and friends between now and the service on Friday.”

Aunt Dinah’s big dark eyes let loose their tears. Her hankie is

damp and Annie offers her her fresh one.

“If I had children I would like them to be thoughtful children just like you three. Your Mother entrusted me with your care and I

am honoured. Now we must help each other get through this awful

time.”

Annie and I realize we have both been holding our breath

when we hear Mary exhale loudly. We both gulp air in

greedily.

Annie says, “I prefer to talk to our Mother alone.’

Mary says, “I’ll talk to our Mother just before I say my prayers tonight.”

I squeeze Annie’s hand. I have a big hard lump in my chest. I

can’t cry and I can’t speak. All I want is for our Father to come

home and make this nightmare go away.

Jan 21. 1872

Dearest Diary,

My name is Sarah Ann Green Collins and I live on

Middleton Road in New Grimsbury. I am named for my mother’s

aunt who lived with our family when my brother George died. He

was just a tot. I was born seven months after he died. I was

supposed to be a boy but God made a mistake and made me a

girl.

I’m telling you this Dearest Diary because this is my private

place. Mother gave me this diary last Christmas. She kept a diary

only until George died so I know my name is not in it. I will sign

my name with every entry and I will make a record of my own

life.

I was disappointed to get a diary, as I wanted a new tea set

for my dolls. Mary had broken the spout off the teapot. You can’t

have a proper tea party with a broken teapot. Mother said, ‘You’ll

put your dolls away soon Sarah. You’re old enough to start

recording your thoughts and feelings. You talk enough for two

children. Put some of those extra words in your diary.’ So I am.

Annie said Mother became very silent after George died.

Father told her Mother would brighten up when the baby who

was me was born but she didn’t. But when she had her

‘remembering George’ days she was very silent and didn’t answer

our questions. That when I started talking to George.

Not the real George. To the George who is our angel in

heaven. Next to Annie he is my best friend now that we have

moved away from Banbury. Now that I have you Dearest Diary I

can let George have a rest from my thoughts. It’s not far from Banbury to New Grimsbury but it feels very far when your friends aren’t just down the lane anymore.

Father will be home from Oxford tonight. Oxford’s not far

from New Grimsbury either but it feels very far when your

Mother had died and your Father is not at home.

Signed,

Sarah Ann Green Collins

“Annie. Mary. Sarah. Come to the kitchen for your tea.”

‘Yes Aunt Dinah’ comes from three different parts of the

house as we three sisters trail downstairs to the kitchen. This kitchen is not as big

as the one at The Bear in Banbury but it has a large fireplace to cook our food and

keep us warm besides. We all miss the inn and the jolly people who came to have an

ale there. Annie mostly misses our cousin Walter Ives. He's Banbury too and is

working hard every day at the apprenticeship his father secured for him beofre he

died last year. Aunt decided to move with us to New Grimsbury. She said Mother was

worn out from the move and could use help getting back on her feet. Now I know that

Mother wasn’t ever going to get back on her feet.

“I was thinking of sending a fly with a message to your

Father in Oxford but I realize that the messenger would likely pass Joseph on the

road. It would be unsettling for him to have to drive the trap back here with the bad

news and the worry of you three girls on his mind.”

I think to myself that we ‘three girls’ haven’t had one

nasty word since Mother passed away. I can’t imagine it can go on forever but it

certainly has been quiet without Mary bickering with us.

Aunt ladles thick beef stew from the cauldron on the hob

into three white bowls. Then she tucks the bread under her arm and cuts three

thick slices. Aunt has made our favourite meal even though she has been busy

with 'arrangements' as she calls them. A funny noise is in my throat and

escapes without my bidding. Aunt turns from the hob and says,

“Sarah come here love. I won’t have you crying into my nice stew.”

She gives me a quick shoulder hug and then turns to wipe down the stove.

“Aren’t you having your tea with us?’ asks Annie.

“You go ahead without me I have a million things on my mind.”

‘Do you think truly our Father will be home tonight? I should like him

to kiss me goodnight and say ‘God Bless’ the way our Mother did,” I ask.

I see Aunt Dinah’s muscles working at her jaw line as she straightens

her back and gestures towards the back door.

“He had better be. This would not be the time for one of his extended

business stays. I swear he thinks more of his uncle’s Pettifer & Sons than he

does his own home.”

This is not like our sweet Aunt. I remember the first morning after our

Mother died. Aunt didn’t let us see her crying and held us close to comfort us.

She has been so sweet with us even when we weep and beg her to bring our

Mother back. I remember how much our Mother depended on her with Father

doing his new traveling job. Our Mother and her sister were best friends just

like Annie and I. I can’t help but wonder who comforts Aunt Dinah now that

her best sister is gone and what I would do if I lost my Annie.

‘That’s not fair to Father. He has to work to feed us and keep the

house,” it’s our quiet sister Annie.

Aunt thuds the bread knife on the table and we all start and lean away

from her. Her eyes drop to her hands as if even she is surprised at the noise.

She picks up the edge of her apron. She pleats it and re-pleats it. After taking a

big breath she speaks.

‘You’re right Annie. I’m sorry to speak so harshly of your Father. It’s

just that I miss your Mother so very much. I’m a mean old bear when people

do not do as I wish. Of course he will be home tonight. Please don’t listen to

the words of a worried old Maid.”

Same awful day Jan 21

Dearest diary,

I don’t know if I am to write in my diary more than one

time each day. I have so many thoughts and feelings whirling

around in my head that I feel I must.

I can’t tell Annie or Mary so I must tell you Dearest Diary.

The day that Father left for Oxford I was sitting on the carpet

behind Mother’s chair. I was playing with my dolls. Father was

wearing his dark grey coat that smells of lambs when it gets damp.

His green muffler was wrapped around his neck so many times

that he looked like a turtle.

He took his leave from Mother over and over again. His

clothes were much too warm for Mother’s room and his face was

shiny. He would barely get to the bedroom door when he would

turn around and come back again to crouch beside Mother’s

chair.

Mother was leaning with her tiny face on a pillow on the

arm rest and her legs were propped up on the hassock as Doctor

had ordered. Aunt had placed the madras shawl around her legs.

Father brought Mother that shawl from London his last trip. The

chair that looked so cozy when Mother would invite us in for a

cuddle now looked too big for a giantess.

My dolls were quite sick that day and I didn’t quite know

what to do about it. I gave them thin broth with a teaspoon but

they kept getting thinner and thinner just like Mother. I was

playing ever so quietly. You must be quiet in a sick room.

I heard Mother say, ‘Just go Joseph. There is no changing

what has begun.’ I heard Father choke out a little sob and say,

‘Maria I love you more than life itself.’ Then Mother said quite

harshly. “Do go now. Go to your business deals. The girls and

Dinah will care for me.’ Now Father was choking on his sobs.

‘Maria please. I can’t leave you with harsh words between us.’ But

Mother said ‘We have only words left between us. Go.’

I wanted to crawl into a hole under the chair. I knew I

shouldn‘t be listening to my parent’s conversation. They had

forgotten I was there. I put my head on my knees and tried to cry

into my skirt but Father heard me. He came around the chair and

lifted me into his arms. I am past ten years old now and I didn’t

think he could still lift me. His old blacksmith muscles are still

working. I was soon on his knee with my head buried in his

greatcoat.

Father had stopped crying and neither he nor Mother said

anything for a great long while. I could hear Mother’s clock

ticking in time with my heart. When it chimed ten o’clock Father

broke the silence.

‘Little one, parents sometimes have harsh words but they are

washed away by tears of love.’ I had the same big hard

lump in my chest as when Mother died. I could only nod. Father

asked me a very important question. ‘I’m off to business in

Oxford but only for two days. Will you promise me something

Sarah?’ Again I could only nod. ‘While I am away I want you to

take extra special care of Mother. Can I count on you Sarah?’ This

time I managed to squeak out a ’Yes.’ Then with a kiss for us both

he was gone.

Now what will I do Dearest Diary? Father will come home

and find Mother dead. Will he think I didn’t take extra special care

of her?

I hear the sound of a horse and trap on the pea gravel.

I’ve been waiting and longing for Father to come home all day. I

want to run to him and tell him I really did take extra special

care of Mother but she died while I was asleep. I want to run to

him but I have that big hard lump in my chest again and my feet

are frozen to the floor.

Signed,

Sarah Ann Green Collins

Labels:

New Grimsbury. Warkworth

Saturday, September 8, 2007

# 1 OPEONGO LINE 1907

CLONTARF, RENFREW COUNTY, ONTARIO

1907

It's about as far away from the English countryside of my youth as I can imagine. Yet

this dusty road feels like an English lane. It's not paved; has washouts where

overflowing steams gain the right-of-way; rabbits scampering in the morning mist and

the crows' cawings worry the air here too. This is where the likeness ends.

Split rail fences wind spider-like at the fields'

perimeters;broken teeth tree stumps cling tenaciously in the middle of crops; log

barns and outbuildings brave the barnyards ever fearful of the encroaching forest

and lonely hayfields and cow pastures peek furtively from behind second growth

conifers thronging the roadside like children at a parade.

But hold a minute. People live here and they do speak English. Of a sort. Not

'The Queen's English' but with pride in knowing the Irish, French and Germans were

here first. They sculpted forests into farms; piled stones praying vainly that no

more would surface in spring and gave the English language a sweet twist.

These same people share joy and sorrow, hope and despair, love and loss, rage and

humility as the Englishman does. And most of all they have children.

Barefoot in summer children; fishing pole children; out early to do their chores

children; walking miles to school children; playing in the hayricks children and children

who have no mothers.

Tom and Mary. These are the two children I have come to mother. I will share my own

four sons’ lives with them. Lives overshadowed by the death of my three husbands and

their one sweet sister. Two are already fine young men in spite of England and two are

yet children. England is dead to me but the loved ones I lost there still haunt me here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)